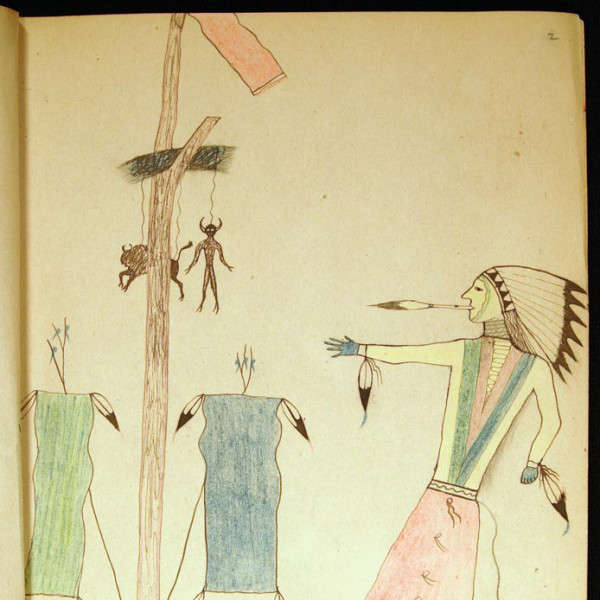

The Lakota are accustomed to hang to center pole of the Sun Dance Lodge two leather figures, one representing a man (often provided with a huge penis) and the other a buffalo. According to the records collected by Walker in the early 1900s, they represented, respectively, iya and gnaski (Walker 1917: 108). The former was a wild giant being, associated with the North and the brother of the trickster (inktomi), while the latter was the buffalo, in its aggressive and inimical aspect. It appeared in the mythic cycle of the original “Buffalo People”, as the “demon of folly and ridicule”, companion of ksa (“wisdom”). But ksa turned himself into inktomi, showing that “Only by closest scrutiny can you determine what is wise and what foolish” (Walker 1983: 277-78, 282). Both images are reminiscent of the idea of disorder, of subversion of the moral and social rules, and of the turmoil aroused in the Mandan Okipa by the arrival of the masked personage representing the disorderly and uncontrolled power of sexuality. As the latter is at last sent away from the village, also the leather images were shot at with weapons until they dropped: at that moment, the young warriors shouted and trampled on the images as they were killed enemies (Walker 1917: 110).

|

Image from Walter Bone Shirt's ledger, realized around 1890, Mansfield Library, University of Montana, Missoula |

The centre pole of the Sun Dance Lodge among the Cheyenne was identified by anthropologist John Moore with a phallic symbol, while the extraction of clumps of sod for the construction of the altar was seen as the exposure of the deepest parts of the earth, which embodied the female generative principle (Moore 1996: 222). In this case, too, the male and female representations emphasize the coexistence and complementarity of two principles, both necessary to allow the flowing of cosmic energy (exhastoz) on the participants and the renewing of the vital forces in nature and society. The leather figure representing a male human which was put on the centre pole assumed oftentimes exaggerated phallic characteristics, emphasizing the aspect of vital and generative power which the ceremony was deemed to pour over the community. In the same sense has to be interpreted the tendency to allow a greater sexual license to the youth during the celebration of the Sun Dance, as it was documented in the XIX century (Kroeber 1902: 15; Walker 1917: 110).

These aspects of the ceremony, aside from the forms of sacrifice of the dancers, constituted the base for the attacks made by the reservation officials and missionaries against the indigenous religions, between the late 1800s and the early 1900s, and that led to the suppression of the Sun Dance ceremony, considered expression of “superstition” and of “degrading and uncivilized acts”.

|

Center Pole in the Sun Dance Lodge of the Southern Arapaho-Cheyenne in Oklahoma in 1893. |