Among the North West Coast peoples, the death of a chief, a leading man or a warrior, implied a voyage to the world above, while the poor and lower ranking individuals went to the netherworld. The corpse was flexed and placed in a wooden box, or sometimes in a canoe, then placed in a tree, in a cave or in some point of the territory. The commoners were buried in mats or blankets and put in shallow graves.

|

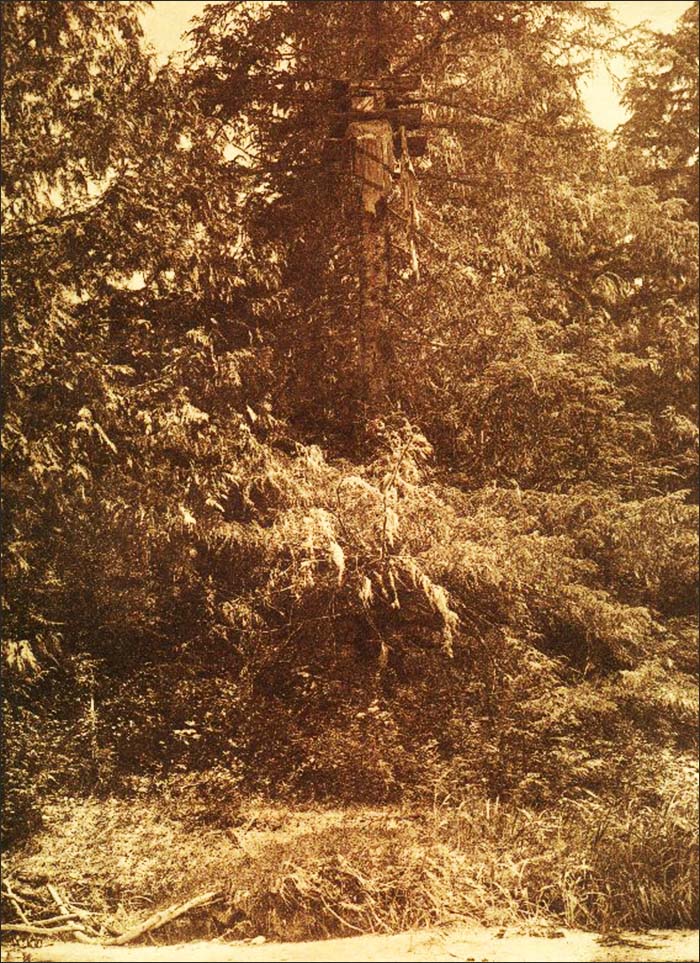

Kwakiutl tree burial. On the top the wooden boards that support the corpse wrapped with blankets can be seen (Photo E.S. Curtis, 1915) |

Mourning, too, was differentiated according to the social rank: it was elaborate for chiefs and nobles, rather simple for commoners. Women began the ritual wailing, which went on for hours, while relatives blackened their faces with painting, cut their hair short, dressed poorly, ate only the strictly necessary and walked with a staff as if they were weak and without energies. In the case of the death of a chief, his achievements were publicly recounted and his personal effects distributed. If the dying wanted some objects with him or her, including the house, these were burned after death, in order that they could follow their owner in the other world. Other valuables could be deposited with the dead.

|

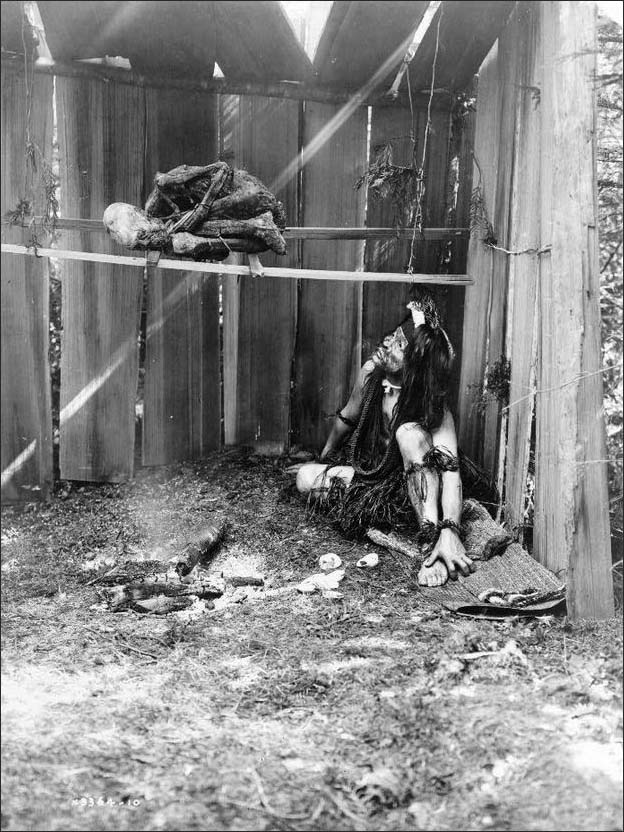

Kwakiutl grave interior. Near the squatting corpse a relative is sitting on a mat and is addressing to the dead (Photo E.S. Curtis, 1915) |

A memorial post, with painting or carvings illustrating the legends of the family, was erected for the high ranking individuals, to celebrate their descent, as one can still observe in the Alert Bay cemetery. Large lavish painted sculptures were sometimes made for a leading chief’s memorial.

|

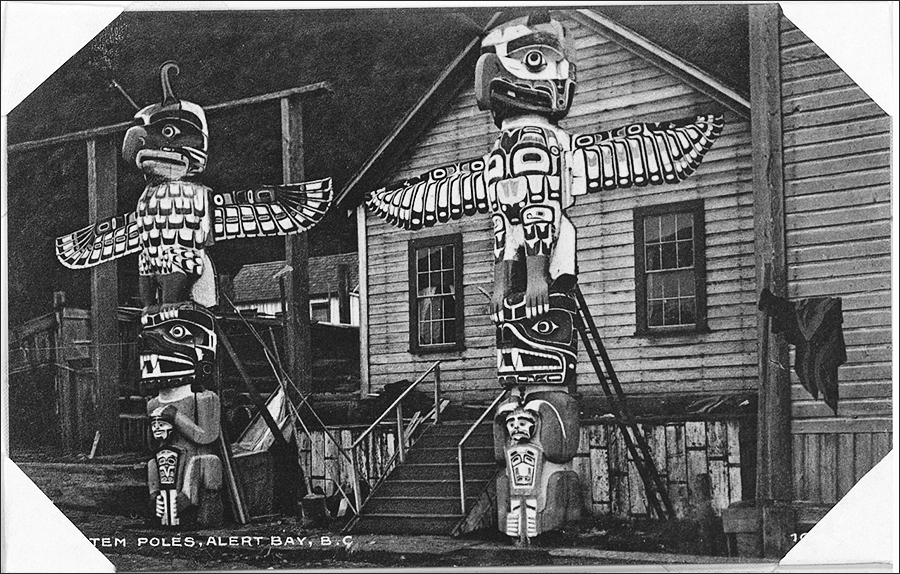

Totem poles erected on high-rank individuals in the Alert Bay burial ground, British Columbia, Canada (Photo E. Comba)

|

After a chief’s death, a feast was celebrated, during which his successor was announced. Later a potlatch (ceremonial distribution of goods and food) was held, during which the old chief’s big canoe was destroyed, titles and privileges were transferred to the heirs and a period of time was established for taboo of pronouncing the deceased’s name. For lesser chiefs and well-to-do commoners, feasts were held with gifts given to chiefs, and the dead person’s name was avoided for a time only by his or her close associates. In ancient times, when a chief lost a close relative such as an eldest son he could kill slaves, in order to make death companions for the deceased in the travel to the land of the dead, or a war expedition could be sent against enemy villages (Arima-Dewhirst 1990: p. 407).

|

Kwakiutl house photographed in the early 1900's showing the totem poles that remember the ancestor who founded the family group and the legends regarding it (National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.) |

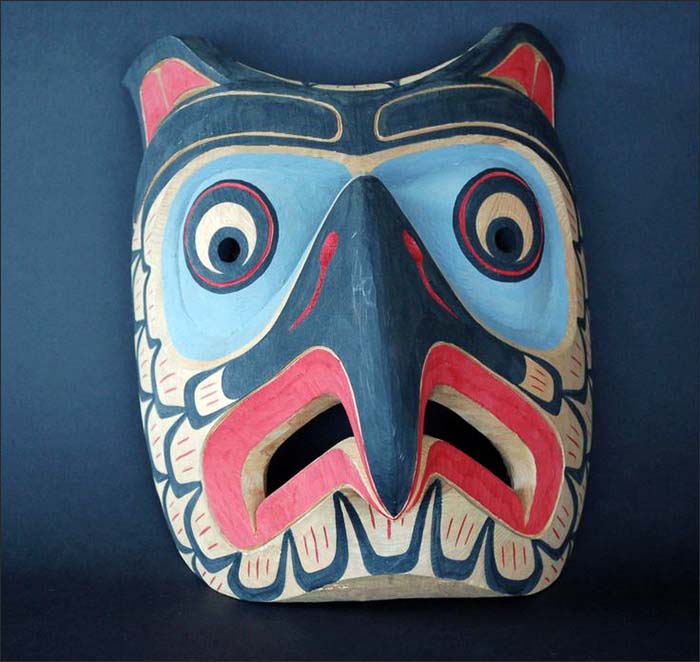

Among the Kwakiutl, the owl was especially associated with death and was regarded as a spiritual double of the human being. George Hunt, Boas’ informant, reported that the villagers of Fort Rupert believed that every human being had an owl mask and that he or she turned into an owl after death. As proof of this, he referred that once he had shot to an owl, on the advice of a Native who claimed that he did not believe in the existence of a link between men and these birds. Nevertheless, this man shortly after died. The villagers were convinced that he had invited Hunt to shoot at his own spiritual double, thus causing his own death (Boas 1930: p. 257-260).

|

Kwakiutl Owl Mask in cedar wood (British Museum, London) |

|