The documents written by the Jesuit missionaries, who established themselves in the Huron territory since 1626, contain a great amass of information about the practices and beliefs of this Iroquoian people as they were observable during the XVII century. They observed that the Hurons did not show particular awe towards death, because they regarded it as a passage to another way of life, not much different from that of the living. When an individual came near the moment of dying, he or she was prepared for the event, even before the definitive leave. The death was publicly announced in the whole village, and the corpse was cared for by the members of a clan different from that of the deceased, thus establishing bonds of mutual aid and exchange between the kinship groups. Just the death had taken place, the ritual lamentations began, while the deceased’s acquaintances gave speeches reciting his/her virtues. Three days after death, the chief in charge of the ceremonies announced the celebration of a feast, at which it was believed the soul of the deceased took part. During it, many gifts were brought around the corpse and were given to the bereaved and to the persons who directed the funeral ceremonies.

|

Reconstruction of the interior of a Huron long-house (Huron-Wendat Museum, Wendake, Quebec) |

The corpse was placed on a scaffold and was accompanied by offerings and grave goods given by the relatives. The missionary Brébeuf claimed that the funerals were so expensive that it seemed as if the Hurons worked and acquired goods only to give away them during the funeral feasts. Usually, the period of mourning lasted for ten days, but the wife or husband of the deceased were expected to mourn for one year: during this time they could not participate in feasts or celebrations, and, of course, they could not remarry. The burials were however only temporary, since every 8 or 12 years all the deceased were disinterred and prepared for the most important ceremony of all, the great Feast of the Dead, during which some villages gathered together to rebury their dead in a common grave.

|

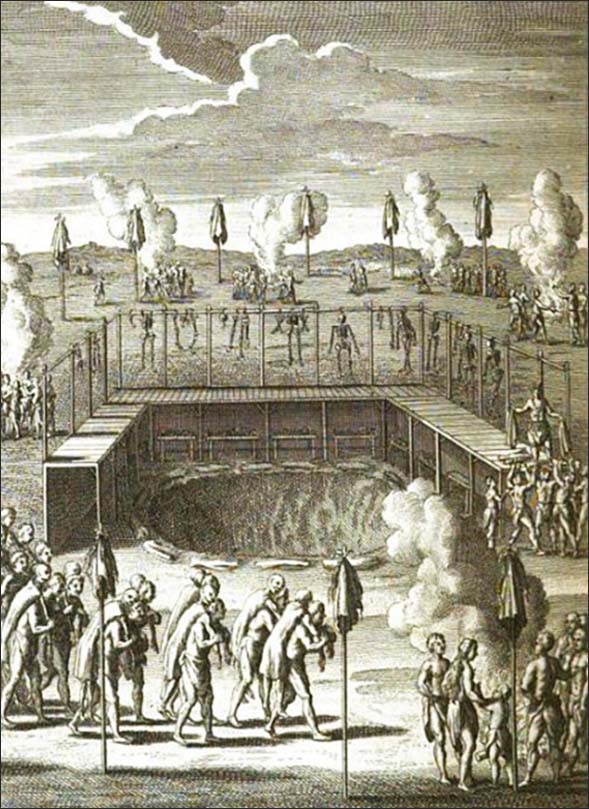

Engraving showing the Huron Feast of the Dead. In the foreground a group of men are carrying the corpses of their relatives on their back, to be buried in a common grave after about ten years from their death (from : J.-F. Lafitau, Moeurs des sauvages amériquains, Parigi, 1724, Vol II) |

The Hurons believed that each person had two “souls”: one hovered around the corpse until the Feast of the Dead, after which it was released and could be reborn in another body. The second soul, after the Feast, departed for the village of the dead, which was located in the direction of the setting sun, in the West. After the Feast of the Dead, it was believed that the souls would assemble, covered with their grave covers and bringing with them their grave goods, and went on the path along the Milky Way. Along the path to the villager of the dead, the souls had to face many dangers and obstacles: a spirit could pierce the skull of the deceased and draw out the brain, or a dog, which guarded the passage on a log across a river, could frighten the souls and drown them. After many months of travel, the souls would finally get to the village of the dead, where they would spend a life very much like that of the living (Heidenreich 1978: p. 174-175).

|

Burial mound attributed to the Iroquoians, Allen County, Indiana

|

Among the Iroquois, very similar conceptions can be found: it was believed that the spirit (or “ghost”) of the deceased participated in the ceremonies following the death of an individual, and that it did not left until a period of ten days was elapsed after death. At this point, the soul abandoned this world and followed the Path of the Souls, the Milky Way. After death, the person was dressed in the “death clothes”, that is clothing of traditional design. Mirrors and other reflecting surfaces were covered with cloth, in order that no one, especially children, may accidentally be frightened by seeing the ghost image in them. A special ceremony, called ohki’weh in Seneca language (Feast of the Dead or Chanters for the Dead), was held annually for all the dead of the community. It comprised tobacco offerings, invocations, dances and songs for the dead. The dancing was clockwise rather than the customary counterclockwise, because it was believed that these dances were not only for the dead, but that the dead themselves came to dance with their relatives (Tooker 1978: p. 462).

|