In the Iroquois communities, the term False Faces designates the members of some ceremonial associations, who wear masks and perform purifying and therapeutic rites during the celebration of festivals, especially at the Midwinter Ceremony. In the Seneca language (one of the nations composing the Iroquois Confederation), the term for “mask” (gagóhsa) signifies simply “face” (Fenton 1987: p. 27).

|

|

|

The most ancient mask of the False Faces, collected in 1850 by anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan (New York State Museum, Albany)

|

|

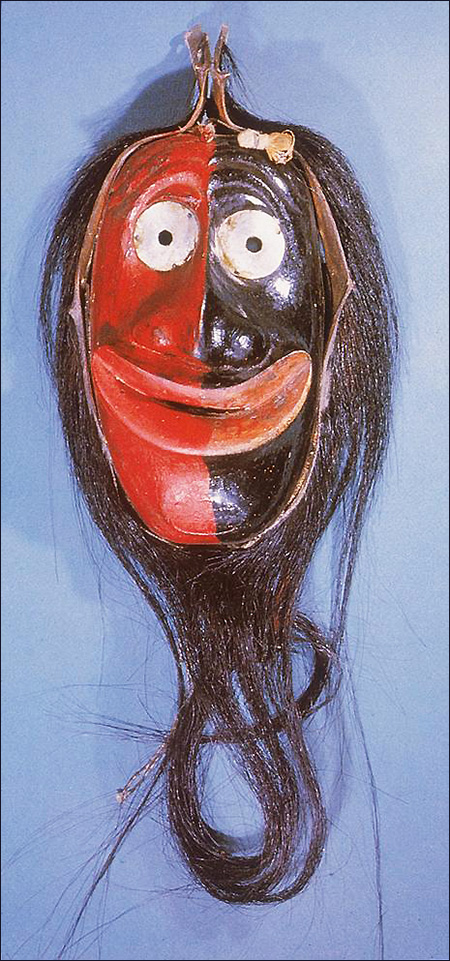

False Face mask, representing the unusual characteristic of a face split in two halves, painted in red and black. Normally, these masks are painted either in black or in red (United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.)

|

The False Faces are the impersonations of mythical beings living in the remote and wilderness areas, at the margins of the known world, on the mountains or roving among the woods; these kind of beings are common to most of American Indian peoples. Several narratives tell of hunters, who, entering woodlands or forests, suddenly find themselves in front of strange beings, with semi-human features, flickering from one tree to the other, or appear as bodiless heads, “faces”, with long wavy hair. Usually, these creatures show themselves to be benignant, provided they are pacified with an offering of tobacco or corn meal. Sometimes they can appear in dreams to the hunter, and it is believed that the first masks representing them originated from these kind of dreams.

False Face mask carved in the wood before the extraction from the trunk (Museum of the American Indian, Washington D.C.) |

|

|

| |

|

|

The association of the False Faces with trees is evidenced by the tradition according to which, ideally, the masks should be obtained carving the wood of a live tree, usually a basswood tree (Tilia americana), following a highly ritualized procedure. It was believed that in this way, after an invocation and an offering had been made to the tree, the forest spirit should penetrate into the mask, imbuing it with his power (Fenton 1987: p. 206-210).

The masked dancers shake their rattles, made with the shell of a snapping-turtle, and rub them on the tree trunks or on the wooden house walls, imitating the prototypical figure of the Great False Face, who inhabits the outmost margins of the world, where he acts as guardian of the World Tree, which stands at the centre of the earth and from which he obtains his powers.

|

An Iroquois mask carver, helped by his assistants, is going to sculpt a mask from the living trunk of a basswood tree (Photo by Arthur C. Parker, 1905) |

|