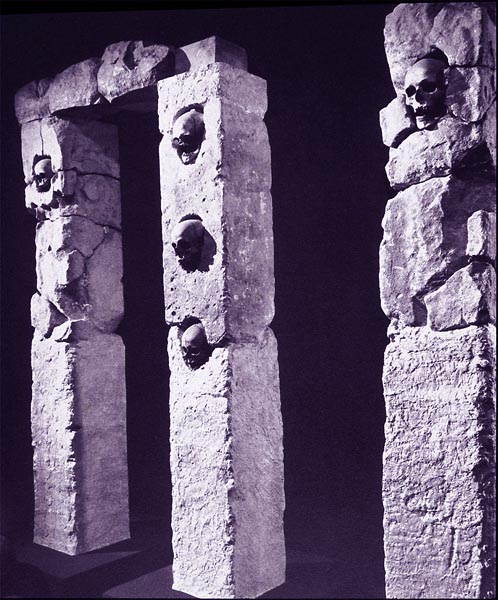

Limestone portal, with niches containing human skulls (about I century

B.C.), from Roquepertuse, ancient Celtic religious site near the town

of Velaux, Provence, and now in the Musée-Borély, Marseille,

France.

The presence of heads separated from the body, also in sculpture, is

a recurrent theme in Celtic art, and has suggested the existence of

a sort of “head cult”. It is likely that the heads of dead

warriors were kept: Latin authors referred (with revulsion) the custom

of Germanic populations, who hang up the heads of slain enemies near

their headmen’s huts or at the horse’s bridles of valiant

warriors. In the Irish epic, the hero Cú Chulainn came back from

battle holding nine heads in one hand and ten in the other. The mythic

traditions emphasize the holiness of the head, referring how certain

heroes’ head, like the Welsh Brân the Blessed, continued

to speak for a long time after having been severed from the body.

The Celts perceived, probably, the boundaries between the world of the

living and the world of the dead as tenuous and permeable: certain places,

like the hearth or the burial place were regarded as points of passage,

through which the deceased could come back to contact the world they

had left with their death. In the most ancient past, the continental

Celts practiced the burial of the corpses, but in a later period they

began to cremate the dead, perhaps influenced by the Romans. Among the

insular Celts, however, there were no traces of inhumation before the

I century B.C., an evidence of the fact that the corpses were cremated

or left to decompose outdoors. Seemingly, the dead did not inhabit a

world radically separated from that of the living, but there was a certain

contiguity, permitting to the dead to enter periodically in contact

with the living. This was allowed above all during the feast of Samhain,

on November 1, when the screen separating the two realms reduced until

it disappeared for a brief period. Marginal or liminary places, like

caves or swamps, were regarded as access routes through which it was

possible to enter in that “other dimension” in which the

dead, the divinities and the spirits lived, and which existed beside

that of humans. In this alternative world, time passed in a different

way with respect to our world, whereby a short sojourn beyond the boundary

between the worlds could mean a period of hundreds of years in the human

world. This explained why those who lived in the invisible world were

not subjected to aging and death. That world was called in several ways:

Mag Mell (“Plain of Honey”), Tir Na Nog (“Land of

Youth”) or Avalon (from Emain Ablach, the “Island of Apples”).

[Image: http://library.artstor.org/library/]