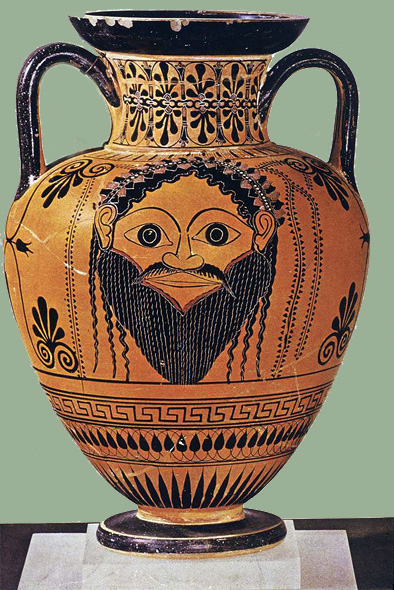

Amphora of Attic production (about 530-520 B.C.), representing the mask

of Dionysus, now in the National Museum (Museo Nazionale Tarquiniense),

Tarquinia, Italy.

Unlike the other gods, Dionysus is sometimes represented in a frontal

way, with his eyes looking directly into those of the beholder. Just

this representation leads to better understand the unavoidable power

of his look, which induces the abolition of the barriers which generally

separate the human from the divine, thus permitting an interpenetration

of the worshipers and the gods. Around him, Maenads in an ecstatic trance,

Satyrs, Centaurs and Sileni move excitedly, expressing with somersaults

and jumps their joyous and discharging frenzy, obscuring in this way

the borders between human and animal, male and female, young and old.

Even Tiresia, the seer, and the king Cadmus, in Euripides’s Bacchae,

who were already old men, let them be dragged by the divine folly. On

the other hand, Dionysus apparitions revealed a manifold divinity: sometimes

in the shape of a child, or of a youth or of an adult man, as well as

in animal or plant shape. Dionysus’s gaze had the power to induce

the manìa (sacred folly) and to compel the one who looked

at him to go outside of oneself. As jean-Pierre Vernant as written:

“Dionysus teaches us or compels us to become something other with

respect of what we are in our ordinary life” (Vernant 1990, p.

103).

[Source: http://library.artstor.org/library/]