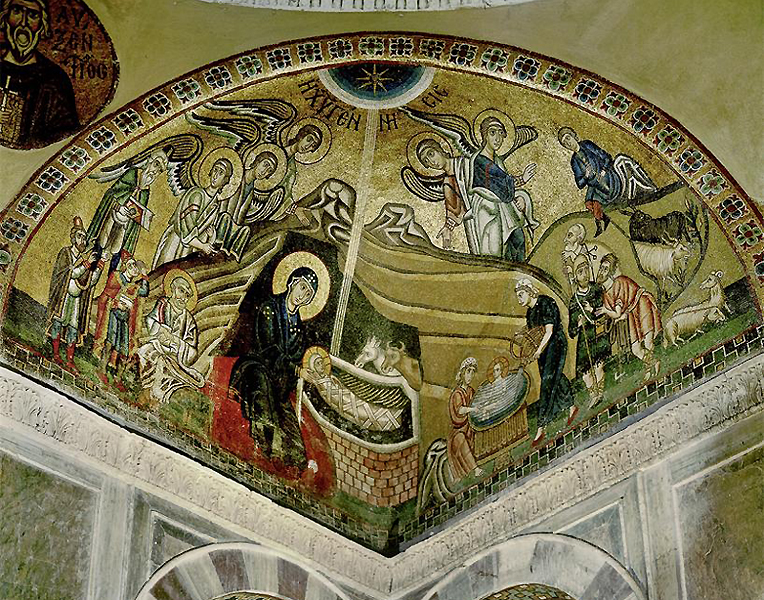

Figure above:

Mosaic of the XI century, depicting the

Nativity, from the Monastery of Hosios Loukas, near the town of Distomo,

Boeotia, Greece

[Image: http://www.kingsacademy.com/mhodges/11_Western-Art/09_Byzantine/09_

Byzantine.htm]

Figure

below:

Giotto’s fresco, from the Cappella degli Scrovegni, Padova, Italy,

realized in about 1305, representing the Nativity.

[Image: http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nativit%C3%A0_di_Ges%C3%B9_%28Giotto%29]

These

depictions contain already all the elements which shall become traditional

components of the Presepio (Nativity scene), first realized by Saint

Francis in 1233: the cave, the animals, particularly the ox and the

donkey, the shepherds, the flocks, the star. The setting in a cave,

which was adopted also by Saint Francis, is rather quaint, in so far

as there is no mention of it in the canonical Gospels. However, it seems

that the cave, as a place of communication with the other world, which

had played an important role in ancient religions and in the mystery

cults, should have exercised a deep influence on the symbolic development

of the Nativity representation.

The most important Christian feast, the Nativity of Jesus, began to

be celebrated since the IV century. In the V century, in Jerusalem,

the date of December 25 was substituted to the previous celebration

on January 6 and rapidly this custom spread all through Christianity.

It came to substitute the Roman feast devoted to the Sun God, the Die

Natalis Solis Invicti, which celebrated the rebirth of the sun after

the winter solstice. The Eastern Churches that had not adopted the Gregorian

calendar continue to celebrate Christmas on January 7. “According

to the legend, Christ should be born at the stroke of midnight: that

is, symbolically his Incarnation should have marked the beginning of

a new era, because the legal day, in the Roman Empire, began with the

seventh hour of the night, that is at midnight” (Cattabiani 2003,

p. 83).

In Northern Europe, the period of the Christmas feasts was called Yule,

term deriving from the German jol, of uncertain etymology, but which

is associated by some scholar with the meaning of “spinning wheel”,

with reference to the duration of the solar day, that, after the winter

solstice, begin again to grow. The feast has maintained part of its

pre-Christian meaning, which has been integrated into the traditions

of Christmas. The period from December 25 and Epiphany was known as

the “Twelve Days”, and it was believed as a moment in which

the evil spirits were particularly powerful, because they tried to hamper

the overcoming of the solstice and the return of light and warmth with

the Spring. The home decorations, with evergreen branches and lights,

was a manner to encourage this crucial passage for the annual cycle

and to defeat the negative forces. A big log, known as the “Yule

Log” was burnt on the hearth and let consume slowly until Epiphany:

the remains shall be used to kindle the new log on the next year. The

tradition of the Christmas tree seems to be born in Germany not before

the XVI century, with the custom of decorating pine trees with candles,

fruits and colored ribbons, but its meaning took on the ancient decorations

anticipating the arrival of spring flowering (Baldovin 2005a).