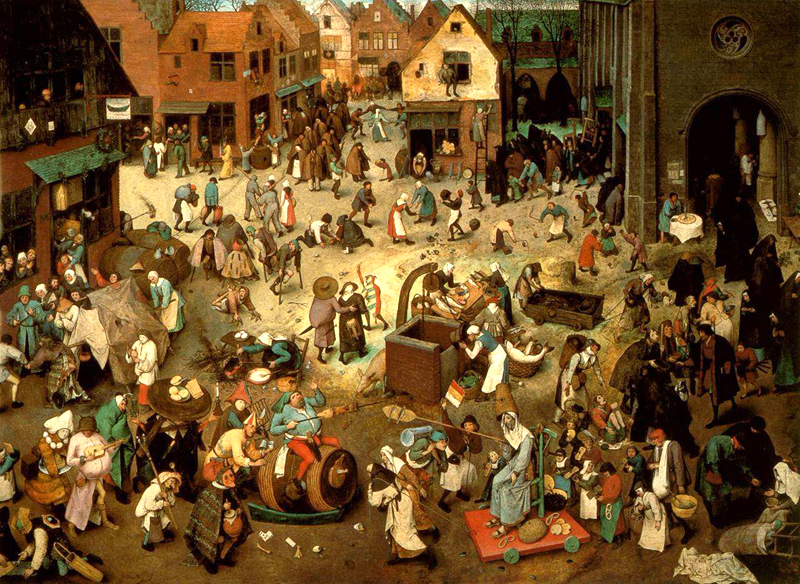

Oil painting by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, realized in 1559, entitled

“The Fight between Carnival and Lent”, now in the Kunsthistorisches

Museum, Vienna.

The new year and spring festivals which, in the course of time, have

been merged in that complex set of folk customs called Carnival, have

always been regarded with suspect and hostility by the Church, because

of their patent connection with pre-Christian beliefs. For this reason,

the Church has committed itself, perhaps even in the choice of the feast

name, to disempower and control the symbolic extension of this feast.

Indeed Carnival (in Spanish Carnestollendas) makes reference to the

period which immediately precedes the imposition of the ban on the consumption

of meat and the beginning of fasting (in German Fastnacht), established

by Lent. This period was thus seen as a sort of introduction (Spanish

Antruejo, from Latin introitus, “entrance, entry”)

to Lent. Folk culture has established thus a symbolic contrast between

the period of revelry, of the “fat” food, of exuberance

and licence (Carnival) and the period of penitence, of fasting, of submission

to rigid moral rules (Lent).

The period of Lent, however, maintains also the character of a preparation

for the spring festival of Easter, and of a purification phase, resuming

the idea, developed in the Roman world, of the month of February as

a period devoted to purifications, understood as a regeneration of nature

(Latin februo, “to purify”). Lent corresponds also

to a critical period in the cycle of agricultural production: the cold

season is not still over and spring is not still begun. “If it

is true that “one cannot” eat fat food, it is also true

that however – since the winter supplies were exhausted –

this could not be done in any case. The dry, light diet, assumed with

spirit of penitence thinking to the forty days spent by Jesus in the

desert, has in reality also its functional good reason” (Cardini

1995, p. 167).

The Carnival festivals have inherited in part the tradition of the Feast

of the Fools or of the Innocents, executed by the young clerics and

students, during the initial period of the year, the Twelve Days between

Christmas and Epiphany, as well as the feasts of the associations which

acted out mocking plays, forms of reversal of social roles and of satire

of authorities and hierarchies. But they resume also much more ancient

customs, ceremonies for the renewal of the seasons, of propitiation

of fertility for the fields and of the forces of nature (Heers 1983,

p. 223). Carnival masquerades represented, in continuity with pre-Christian

religious beliefs permeating the mentality of medieval humanity, also

a personification of the dead, returning in the moment of the yearly

cycle which anticipates the resurgence of the vital and generative force

corresponding to the spring season. From the earth emerged those beings

that possessed human, animal and plant attributes, figures which are

amenable to that of the Wild Man. An indication of this connection between

life and death can be found in the typical foods of the Carnival period:

pork and the broad bean (fava bean). Behind the banquet of pork there

is a death ritual: the slaughtering of the pig as a sacrificial action

and the animal’s testament (the latter appearing in popular literature

and constituting a variant of the Carnival’s testament, who is

condemned to death). The broad bean, in its turn, is a vegetable which

belonged to the realm of the dead (according to the representation of

it that was diffused by ancient Pythagoreans). The two foods together

are remained as the traditional dish of the New Year evening, the “zampone”

(“pig’s foot”) with lentils, which continues to be

regarded as auspicious for the next year’s prosperity (Cardini

1995, p. 191-192).

[Image: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Der_Kampf_zwischen_Karneval

_und_Fasten_%281559%29.jpg]